Familiar Enemies

January 16, 2025 Asian Arms

Dha and daab are often grouped together by western collectors, often misspelled as 'dah' and invariably assumed to be Burmese. Collection records are often spotty at best even with museum pieces and a record of a country where something was acquired in fact says very little regarding its true origins. This is in part because the vast majority of dha/daab on the antiques market came through the UK due to their colonial connections to the area, or via France and their colonial territories in modern day Laos and Cambodia.

Swords travelled widely, both via their owners and the campaigns they participated in as well as the fact that the many wars and campaigns between the Burmese kingdoms and the Thai kingdoms were not conducted by monolithic militaries, but rather comprised various groups who owned allegiance or suzerainty to one side or the other. This meant that you could find nobles and their retainers fighting for the opposite side in some cases. The political realities of southeast Asia were that many cities and regions changed hands between stronger central powers like the Konbaung and Toungoo dynasties of Burma, the Ayutthaya kingdom and Lanna. Many of these areas were controlled or influenced by these central powers at various points and would be called on to provide military aid for campaigns. In a practical sense this means that a military force from a place like Chiang Mai could at times be fighting on the Burmese side, or the Thai side depending on the period.

Because of this complex web of military participation by many different regions and cities as well as the large distances that campaigns covered it is not surprising that swords originating very many areas were in fact spread across the entire region of Southeast Asia. In essence this means that a northern Thai sword appearing in colonial Burma was not an oddity but rather something quite logical, while a Burmese sword appearing on the Thai side of the modern day border is also hardly shocking. The simple reality was that the combative sides were not nicely decked out in neat uniforms and regimented equipment like a Hollywood movie.

Despite this tangled web of peoples, armies and political allegiances we can still make broad attributions where a sword was likely to originate from, looking at details of how it was manufactured, materials used and a variety of other factors.

The two swords that are the subject of this article are an excellent illustration of this fact. Both are of a type that can be found in modern day British museums and would be invariably labelled as simply "Burmese". This is in part due to the assumption of the former India museum collections (founded and maintained by the British East India Company for many years) into other British museums. Poor collection notes and a lack of interest during the colonial period to actually learn anything about these weapons has contributed to a use of blanket labels and wrong attributions.

In fact the two swords depicted here are from entirely different families, using different materials and techniques and undoubtedly made by different ethnic groups. The first sword, with a pointed blade, steel fittings and a hardwood handle is undoubtedly Burmese. In this case, on of the key indications is the geometry of the blade.

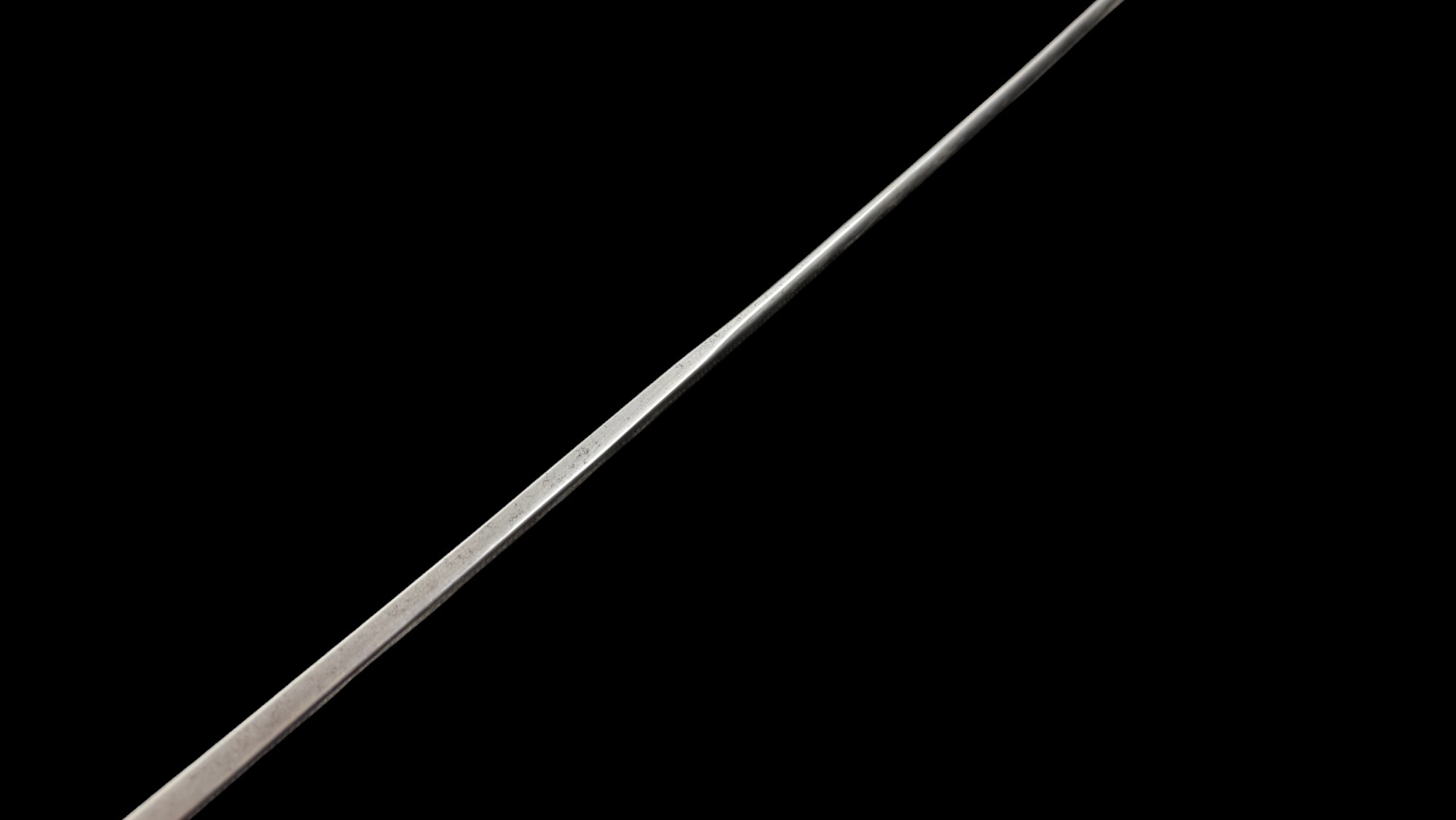

While a small fuller runs the first third of the blade from the hilt, what is less apparent at first glance is that the blade in fact has a second fuller, a shallow almost hollow ground fuller, for the majority of the blade.

This is not a technique common to Thai or Laotian swords, which may use small, groove like fullers, but almost never broad fullering of this style. The spine geometry is flat for the first two thirds of the blade transitioning to a v-ridge for the last third.

These elements on their own are not unknown in Thai or Laotian daab, but more commonly adapt one style or another, rather than a combination of geometries in one blade.

The hilt is simple, relatively short and conforming to proportions often seen in Burmese swords. The mounts are iron, brazed together using brass/copper and very sturdy, while the grip is tropical hardwood.

.jpg)

The sword is relatively large at 94cm long with a 68cm blade and weighing 840g.

In contrast, the second sword is entirely different in profile, dimensions and construction. Shorter, at 89cm with a 51cm blade, but with a similar weight of 829g, it has a completely different feel in the hand and technique required to wield it.

The tip is a spear point style, that while rounded, is sharp. The blade profile is flat, with no fullering and visible signs of quenching and hardening along the blade's edge.

The spine is flat, and does transition to a narrower spine some two thirds of the way along the blade, in some ways similar to the previous example, but in this case does not change geometry and remains flat or only slightly rounded until the the tip.

The grip is again hardwood but mounted with sections of samrit, an alloy popular in Lanna and Siam that mixes elements of bronze, copper and precious metals to achieve a character and lustre at times similar to gold.

The pommel is capped in a similar manner with a long tube of samrit.

The point of balance is markedly different between the two swords, with the Burmese example having a PoB nearly a quarter of the way up the blade from the handle, while the second example balances very nearly at the junction of blade and handle.

The second sword does not then conform to the style of Burmese (meaning Bamar ethnic) swords, but rather shows characteristics common to many Thai and Lanna swords as well as elements that some collectors identify with the Mon people, who had a long standing history of conflict with the Bamar. Given the major population shifts in the 18th centuries between the traditional lands of the Burmese kingdoms, Ayutthaya and Lanna, this sword can be said in a way to be a likely product of something of a melting pot of cross cultural influences and most likely originates in the areas north and west of Ayutthaya and it's associated cities like Kamphaeng Phet, closer to the modern day border of Myanmar.

Swords like these undoubtedly clashed within these border areas during the many conflicts between the Konbaung, their tributary Lanna states and Ayutthaya and it's associated cities. Areas like the Mae Lamao pass (modern day Mae Sot), or the Three Pagoda Pass which were main invasion routes and to this day have very mixed ethnic populations of Bamars, Shans, Mons, Thai and many other ethnic groups. While they originate on different sides of a centuries old conflict, both swords are cousins in a way, entirely different but with a shared past.

When researching swords like these it is important to not blindly assume that references such as museums can always be trusted, but rather examine each piece on its own merits, taking into account the wide variety of sword forms, peoples and influences found in these regions. We can rarely be sure of an exact attribution for a particular sword, but with a little diligence we can often uncover clues that point is down a path to further discovery and insight into the history not only of each sword, but of the cultures and people that produced them.