Barges and Swordsmen

March 1, 2024 Asian Arms

Rivers are the highways of Southeast Asia. In a region covered historically in dense vegetation and jungle, travel was difficult overland and waterways played a key role in commerce, warfare and political control. The great rivers of Southeast Asia such as the Mekong, the Chao Phraya and the Irrawaddy, were trafficked by not just local merchants but European ships, Chinese junks and merchants from all over the world. Controlling these river systems meant controlling their rich commerce and the ability to quickly move troops for military campaigns.

Their importance meant that inland navies were developed by the rulers of the regional kingdoms, including Burma, Siam, Cambodia and Laos. The importance of river boats and barges dates as far back as the Angkor period with reliefs depicting battles on the great Tonle Sap between Khmer and Cham forces, the latter having sailed up the Mekong to the inland lake.

A Khmer boat with warriors (source: Nautical Angkor: An iconological study of Khmer vessels in Angkorian bas-reliefs by Veronica Walker Vadillo)

Elaborate royal vessels were constructed for rulers and accompanying formations of guards would protect the royals in accompanying smaller boats, with both rowers who were armed. We are fortune enough to be able to observe this in early film footage from British Pathe in Burma, the following clip depicting a visit from the Indian Viceroy Lord Reading to Rangoon in Burma.

The royal barges could be quite large, utilise multiple hulls and feature ornate carving as seen in the period illustration of a Burmese royal barge.

(source: The British Library)

Burma and Siam maintained large fleets, at times hundreds of river boats. Because of the specific function of river boats and barges and the troops required to man them, suitable weapons were also devised. Modern day participants of Thailand's river barges wear swords of a hilt pattern that dates back to the Ayutthaya period, slung over the back and straight.

(Source: Thai Navy)

The swords that are the subject of this article conform broadly to this style, although the detail of their fittings is slightly different, with a lotus bud pommel. However the hilt furniture is gold plated, a material usually associated with royalty.

These swords came out of an old Oxford estate and were sold with two daggers or short swords with antler and silver fittings which are of a style that are common to Shan and Karen areas of Burma. I have been fortunate to source other early Burmese swords from similar estates and it seems likely that due to these factors, these swords were collected by someone in the British colonial period in Burma. However they are not Burmese.

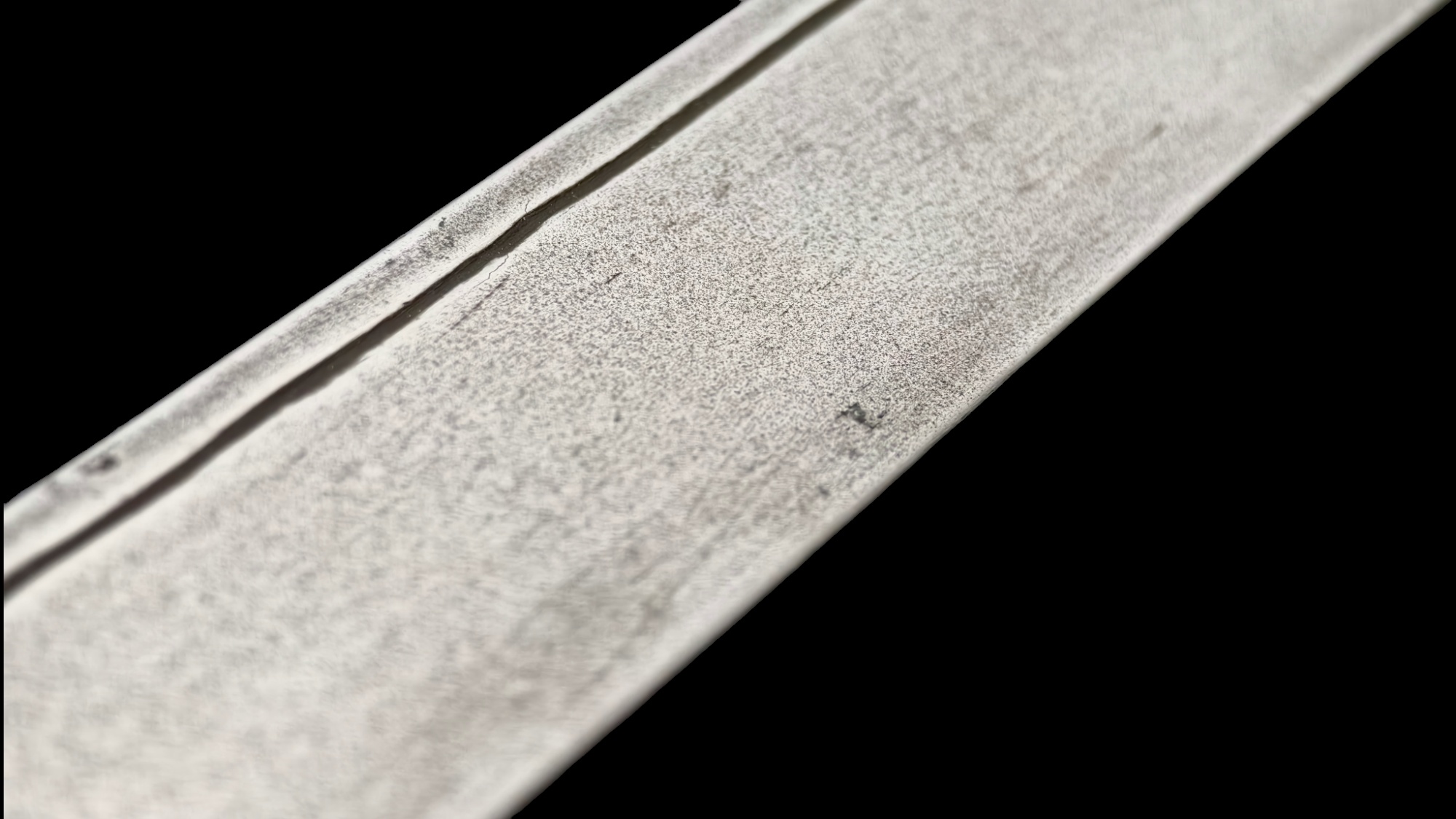

The swords are unusual for several reasons. Straight bladed dha are unusual, the swords are typically curved and are designed for slashing cuts, straight bladed examples are rare. The style of the handles and the length both suits use in confined corners and are similar to known Siamese examples. Finally the colour and texture of the steel used is similar to known examples of 'Lek Nam Phi' a specific iron ore in Siam which is only found in two mines. It is characteristically dark, almost blue in certain light, and is said to have specific properties of hardness and resistance to rust. The fact that the mines were under royal control is a testament to the importance of the ore historically as a strategic resource.

As with many aspects of legendary ores it is difficult at times to sift the fact from the mystery, but the unusual elements of these swords add up to a compelling case for high end steel having been used given the gold plated fittings. A further indication of the value of these blades can be seen in a forge welded repair on the blade of one of the two swords. This is a difficult repair for even an accomplished smith and has been masterfully executed in this case. It was obviously seen as worthwhile to preserve this sword, indicating it's value.

The regional indicators of these swords, the possible connection with Thai ores, their possible collection within modern day Myanmar, perhaps even as trophies from a prior Burmese campaign leads to a confounding myriad of attribution possibilities.

If they were in fact collected in Burma and the knives at the same time, this may point to the border of Burma/Myanmar and modern day Thailand. The blades of the knives that were sold with these swords correspond closely to a type known around lake Inle and the surrounding regions. Given that these swords could have belonged to river based military troops, the immediate suspect becomes the Moei river, which forms a long border both currently and historically between the two states.

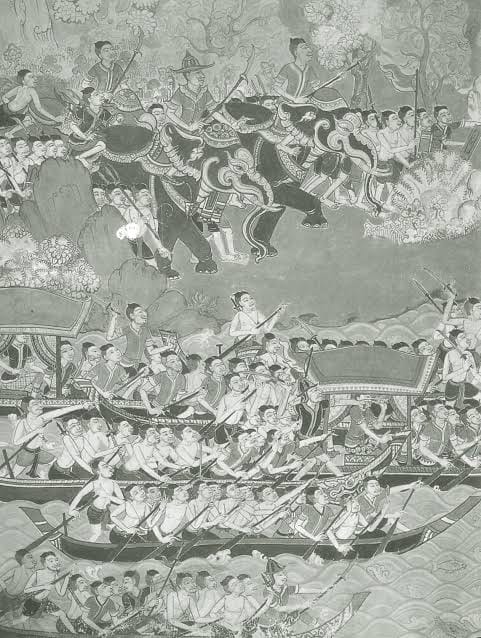

A mural from the Thonburi throne hall depicting a Siamese flotilla attacking the Burmese in the 18th century during the rule of Taksin the Great

However, it should be noted that the hilt features of these sword do not conform to the typical late 18th and 19th century styles of the Thai royal barges. This opens the possibility that they are in fact from a neighbouring country. The Bon Om Touk festival is a Khmer tradition that is considered to date to the ancient Cham invasions and subsequent battles on the Tonle Sap. However it is more likely that the modern form of this event is due to the naval battles between the Khmer and Dai Viet (modern day Vietnam) in the 16th century.

Another possibility is that they are simply a unique pair, commissioned by a high ranking officer or bodyguard with the funds for such a project and the rank to carry gold decorated weapons. Certainly they are a 'matched' pair and designed to be dual wielded. While this is a style popularised in modern movies, it was in fact a difficult skill to master and best suited to shorter swords like these. A notable example in the context of barges who apparently mastered such a style was Phan Thai Norasing, a legendary steersman in the late 17th and early 18th century in Ayutthaya. Modern day medals and coins depict an accurate costume for the period with twin swords with pommels very much like these. While such modern depictions are not "proof" for the pair under discussion it adds valuable insight into how such swords were used and by what kind of soldiers.

(1).jpg)

A 20th century medal depicting the famous steersman at the stern of a barge with twin swords strapped across the back

It must be said at this point that there is no definitive proof that this sword pair is in fact associated with barges and war boats. Rather it is an assumption based on the form and style of the swords. Much of dha/daab research is sadly a case of informed opinion rather than certainty. Other straight bladed Siamese swords include Ayutthaya revival styles in the 19th century, such as this example sold some years ago by a friend. Made during the reign of Chulalongkorn for the royal guard.

.png)

(Source: private collection)

While others in my collection may not be entirely straight but are not particularly curved.

However, with those caveats being said, it is worthwhile to examine the detail of the twin swords in question.

One sword is marginally larger measuring 71cm in length with a 51.2cm blade and a spine thickness of at the base, both are substantial and relatively heavy swords at over 650 grams each.

The hilts are cast bronze with gold paint with lacquered hardwood (most likely rosewood) handles. The pommels are a typical lotus bud style with grip rings, a motif echoed by the other cast mount, with a slight swelling leading to the guard. The wood grips are also carved with a slight swelling providing a solid grip.

The blades are unadorned excepting a single fuller and terminate in a sharp point capable of a thrust.

The blades are set using kithai resin in the manner usual for dha/daab.

The blades are set using kithai resin in the manner usual for dha/daab.

The blades are sharp for their entire length and beautifully forged and finished.

The steel is heavy and shows a particular coloration and texture.

The steel is heavy and shows a particular coloration and texture.

Under certain light the coloration is tinged with blue. The hilt fittings show significant age of a type that unless artificially treated, takes many decades to produce.

Under certain light the coloration is tinged with blue. The hilt fittings show significant age of a type that unless artificially treated, takes many decades to produce.

The spine of one sword is also marked, perhaps to indicate it is for the left or right hand.

The overall fit, finish and feel in the hand of both swords is exceptional with excellent balance and edges that show use, but retain their sharpness. A sign the pair was well cared for during their working life.

When purchasing these swords I would have been quite happy with a 19th century attribution. However having handled them and examined them over several weeks I have become more and more certain they are more likely to date to the later part 18th century and are in fact part of the period of great upheaval across the region during the Burmese campaigns, the fall of Ayutthaya, the troubles in Vietnam during the Tay Son rebellion, the Burmese campaigns of the Qing, and of course the increasing influence of European Colonial powers. Of course this dating is subjective and they could simply be early 19th century, however as a collector fortunate enough to have handled other 18th century pieces from this region, my opinion is not entirely uninformed.

The fittings in particular standout, bronze/cast fittings are not unusual for dha/daab, but the detail is often clumsy, unrefined in terms of finish or braising of the individual pieces. However these are uniform, with well polished surfaces and despite areas missing the gold finish, I dare say beautiful. This is a sentiment that is difficult to convey via an article, but the old collector's saying that there is no substitute for handling pieces in person perhaps holds true here. The quality here is exceptional.

I consider myself as someone in a constant state of learning regarding antiques and particularly swords from Southeast Asia. Anyone who presents themselves as an expert is somewhat suspect for the mere fact they attempt to portray a visage of authority in an area notoriously difficult to establish even a baseline of uncertainty. However, I can say with some confidence that having been fortunate enough to handle many pieces from this region, this pair stand out as the most interesting, unique and perhaps old items I have handled in quite sometime.

My passion for collecting is driven by research and while these swords may remain an enigma for the moment, it is that mystery that gives me a drive to continue to learn and delve deeper into the past of these unique and fascinating regions. While I often share items on these pages I consider I have had some success in identifying, I am proud to publish these as a pair of swords I am emphatically unsure about but confident they represent a significant touch point for future research.