.jpg)

A Nomadic Collar

October 9, 2023 Asian Arms

This may sound like a strange title but as with many of my articles and musings, this is an attempt to paint a picture, through a small physical characteristic of a sword, of a wider interconnected world of trade, warfare, and cultural exchange. In this case the title is a bit literal as the collar under discussion quite literally migrated across large areas of the globe. The sword I will use to illustrate this is an early example likely from the northern regions of Thailand where the modern day borders meet Laos and Cambodia. It has a beautiful heavy bronze hilt and an elegant blade. The standout feature however is the presence of a ‘tunkou’ or collar on the blade. Perhaps best known as a ‘habaki’ in a Japanese context this is a feature that is encountered on occasion in southeast Asian dha/daab swords.

.jpg)

The sword itself is a remarkable example in terms of the form and function but the ‘tunkou’ is an interesting chance to tell a story of how a tiny detail can in fact give great insight into the cross-cultural influences within an otherwise quite localized form.

Collars like this are not typical but not entirely rare within dha/daab. Most often encountered on locally produced versions of the iconic Japanese katana, the result of 16th and 17th century influence with an influx of Japanese traders and mercenaries in the region, the feature is in fact far older with more diverse roots.

.jpg)

The generally agreed source of these collars or the earliest encountered examples are from sabers of the central Asian steppe and appear on swords across diverse tribal groups such as the Magyars, Avars, Kipchaks and many others; generally grouped as so called Turko-Mongol swords. The enormous impact of steppes groups both on Islamic society but also China led to the proliferation of this quite specific design feature.

(source: Wikipedia)

It is likely that it became widespread within a Chinese context after the Mongol invasions, although Steppes sabres were known in China prior to that, and this feature can be seen on earlier ‘dao’. The influences introduced within the Yuan dynasty continued within the Ming and Qing dynasties. This in turn perhaps provides a vector for the feature reaching southeast As after the Mongol invasions of Dai Viet (modern day Vietnam) and Burma.

Certainly the ‘tunkou’ is an adopted design feature within the context of dha/daab and the less than universal use of it seems to indicate it was more of a stylistic choice than a functional one. It is also important to note that the Mongols employed many nationalities in these campaigns from across central Asia which further supports the idea of the diffusion of Steppes saber elements into these regions.

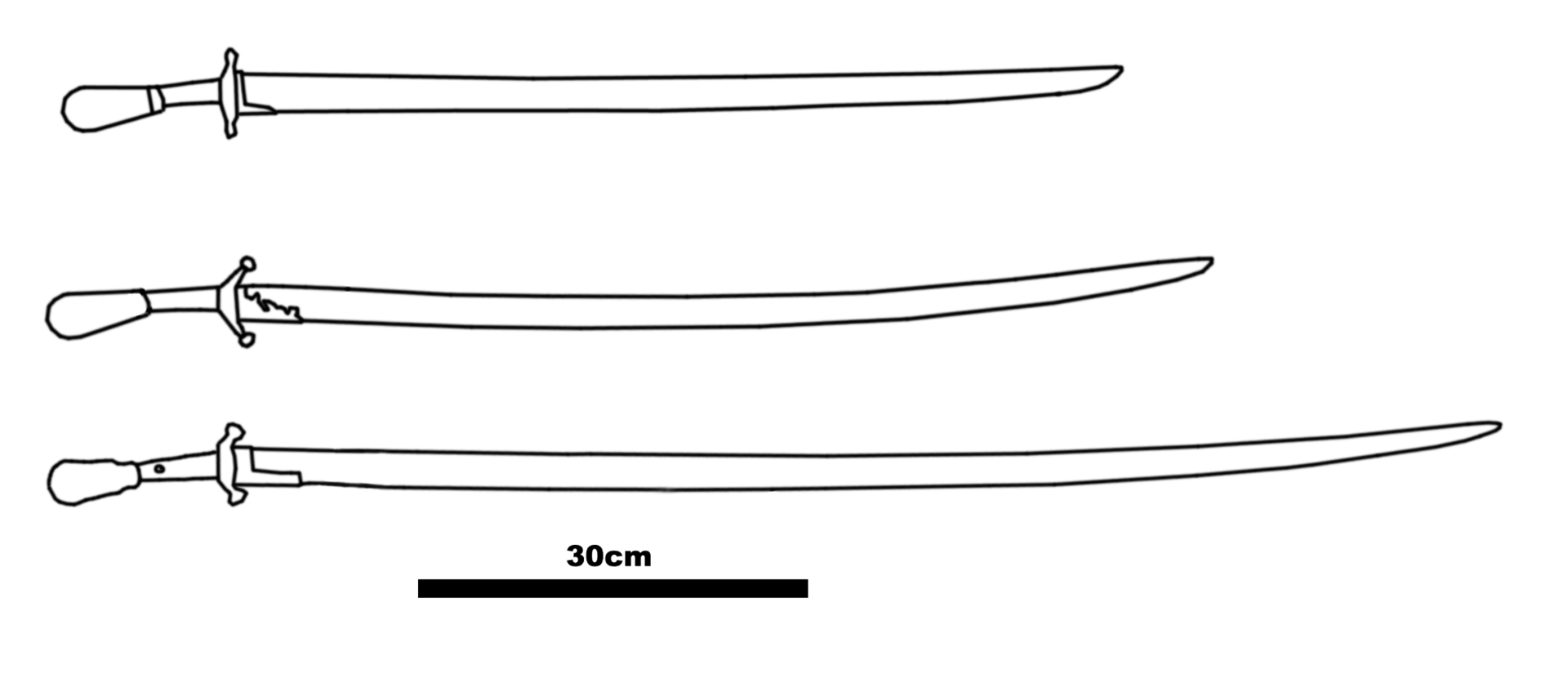

The notched design of this example clearly derives from the Steppes form, exhibiting a derivation of the extended lower ‘limb’ found on Steppes sword collars, rather than the Japanese style where the shape is essentially rectangular.

.jpg)

The hilt itself is a complex set of parts all cast in bronze, with a guard, 5 grip elements and a pommel with an additional plate between the ‘tunkou’ and guard, perhaps in imitation of a Japanese style ‘seppa’ or spacer. The guard features cutouts remeniscent of guards found on Chinese dao and also a fairly common style on Vietnamese swords, in turn likely due to Chinese influence.

.jpg)

The blade is of a style commonly associated with Lanna and Lao swords with a V shaped spine and a blade that flattens and widens at the tip. It is a thick and substantial blade showing signs of long use.

.jpg)

While the pommel is of the 'lotus' bud style often seen on these swords, although in this case a rather simple version due to the cast construction of the sword. The entire hilt features a deep patina and also had areas incrusted with sand/dirt perhaps pointing to the sword having been buried at some stage of its life.

.jpg)

This example fits within a group of dha/daab swords that occur both within the areas of the former Lanna kingdom as well as Laos and are broadly characterized by blades with V spines, flared guards, and relatively short hilts in proportion to the blades.

These swords likely drawn on a mixture of Tai (meaning the peoples who populated Laos and Thailand) as well as Khmer traditions mixed with experiences and influences derived from encounters with the Mongols and other invaders. In general as I have discussed in previous articles southeast Asian kingdoms and peoples were not adverse to assimilating the characteristics of other cultures they encountered and this extended to their arms and armour. While we often think of this period of outside influences occuring primarily once Europeans sprung open the Indian ocean and distrupted the long established economic and power structures of the entire region, in fact the flexible and adaptive attitude to cross cultural contact has been a feature of southeast Asian warfare from a far earlier time.